Since the 1980s, rent has been rising steadily in urban areas. In the UK, we now pay nearly £60 billion in rent each year collectively. We spend on rent only slightly more than we do on mortgage payments.

Londoners will guess that the capital has been behind a decent share of this growth. Wealth inequality, gentrification, and environmentally costly developments are all a by-product of an expanding private sector.

No surprise then that more of us interested in community-led development, including housing co-ops in the past few years. Although their growth has stalled since the 1980s, co-ops are now increasingly attractive to people who would normally be paying private rents for an average of 15 years before they scrap together a mortgage deposit. But co-ops also offer solutions to social problems such as isolation and getting your work-life balance perfect.

Last month, I sent some questions to Sun Coop. A group of friends, whose experience of co-operatives and shared living, has compelled them to launch a housing project. Sun will build their own homes around a unique design that will challenge the standard nuclear family model of living. It will also be a community development owned by its members:

“We are essentially a group of friends living in London. Some of us met through being involved in a co-operative educational project together, and I suppose the more you think about collectivising resources, you start to think about ways this approach could be used in other areas of your life. The catalyst was finding two derelict houses in 2017 and approaching the owner about selling them, since they had been empty for so long. We heard nothing back – which is of course symptomatic of the way people treat buildings in places like London – as investments rather than homes. Obviously rent in London is so high – it’s such a high proportion of the average income especially if you are self-employed, partially employed or in precarious work. So it was important for us to look into why housing provision is so unequal here, and how the quite fertile cooperative housing and squatting movements of the 1960s and 70s have been dismantled somewhat over time.

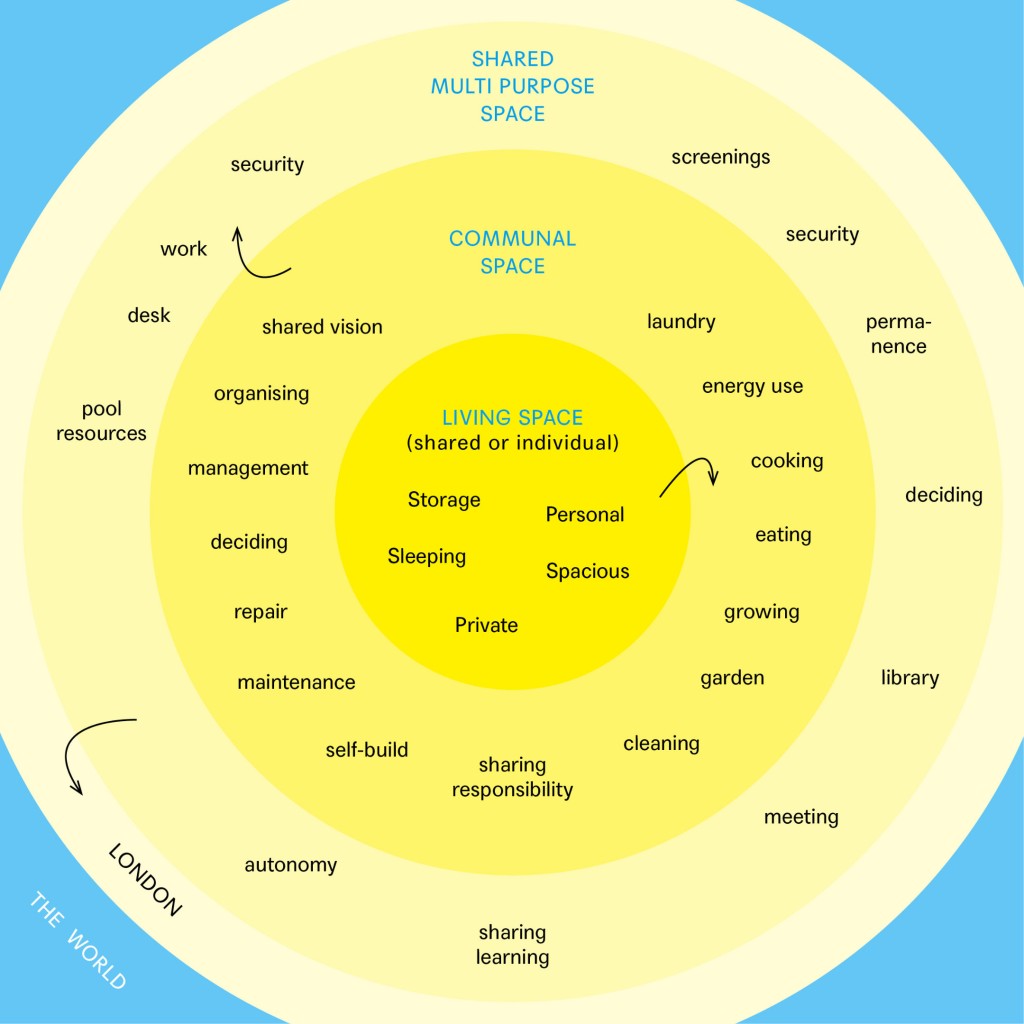

Sun not only wants to break into the housing market. Members have been also been speaking to the architectural consultants Dogma, who builds resources about urban architecture and shared living. The layout of Sun’s living spaces aims to encourage shared autonomy over work and rest. Private living spaces will be adjacent to shared residential and work areas:

“Again, part of this idea was a reaction to the London context. Some of us are designers and programmers: workspaces are expensive and hard to find, and often the providers of such spaces are involved in dubious practices of redevelopment or gentrification. Some of us have to travel a long way for work and pay a lot for travel (before Coronavirus anyway!), and are disconnected from our local area. But our ideas were primarily influenced by our discovery of Dogma’s book Communal Villa, which sets out a simple plan for meaningful shared space – whether for making things or having a business – as a part of a residential building, rather than seeing work and life (production and reproduction?) as two unconnected activities. That said, we want to maintain the boundaries between leisure and work, not to have work invade our homes or evenings or weekends.

Government has provided some support to this type of residential development. Last year, the Major of London launched a £38 million fund for community-led housing with the stated aim of “enabling Londoners to play a leading role in building new social rented and other genuinely affordable homes”. Some has gone to support Community Led Housing London, which in turn helps co-ops. I asked Sun if they have had any trouble finding sites for their development:

“We have had no trouble finding sites, it’s just everything that comes afterwards is the problem! We have had generous support from Community Led Housing London and also from CASH CLT which has given us access to tools to discover ownership of potential sites and read through past planning applications and decisions. We have a few sites in mind, but it has taken a long time to understand what sorts of sites are more possible than others. Often people say to ‘think like a developer’, but really it seems to be about finding sites that most developers would overlook, with architectural or environmental quirks that wouldn’t be worth their while to work around. Also, there are particular London boroughs who are more open to community-led housing schemes, and there are some who do all their housing development themselves, for instance. But pretty much all of them have committed to building new residential homes in their Local Plans and Strategies.

Community Led Housing London lists many more emerging projects like Sun on their website. These developments are not only community-led but several are adapted for the needs of their residents – such as older, LGBT+, or intergenerational households. For some of Sun’s members, the pandemic has laid bare the advantages of shared living:

“Many of us already live in a shared house and (personally)* I have found it a comfort to have others around, to cook in rotation and generally digest what has been happening in the world. Obviously, it has not been an easy time for anyone, but it’s clear to see how during the first lockdown the idea of mutual aid became a necessity for many of us on different scales and I don’t see why this wouldn’t be the same within Sun Coop as a ‘household’ of up to 40 people.

We want to live with people of different ages, and different backgrounds, and to share and develop communally. Our timeline is in flux as we continue with site research. Every aspect of this work is dependent on something else, so it’s not necessarily had much of an effect on us in that way. With the new Government planning rules though, it remains to be seen how these will affect us, whether developments will fall through that allow smaller grassroots initiatives to actually do something, or whether it will be a free-for-all for more expensive developments that end up empty. With the current government we’re not hopeful, but we are determined either way!”

Thank you to Sun Coop for answering questions about their experience. You can visit Sun’s home on Github here and find more advice and case studies on housing co-ops in London here.